Video Logs as AI-Resistant Assessment: The Embodied Alternative

Deep Dives Into Assessment Methods for the AI Age, Part 2

For centuries, written text served as our primary proxy for cognition. If students could construct coherent arguments, marshal evidence, and structure narratives, we assumed they possessed the underlying cognitive capacity to produce such work. Large Language Models have severed that assumption. AI can now mimic critical thinking without the substance of cognition, producing polished prose that exhibits all the surface markers of understanding while requiring no actual learning from its human user. As a result, many traditional assessment methods face a dilemma: they now demand levels of surveillance and forensic analysis that prove both resource-intensive and adversarial to the educational relationship.

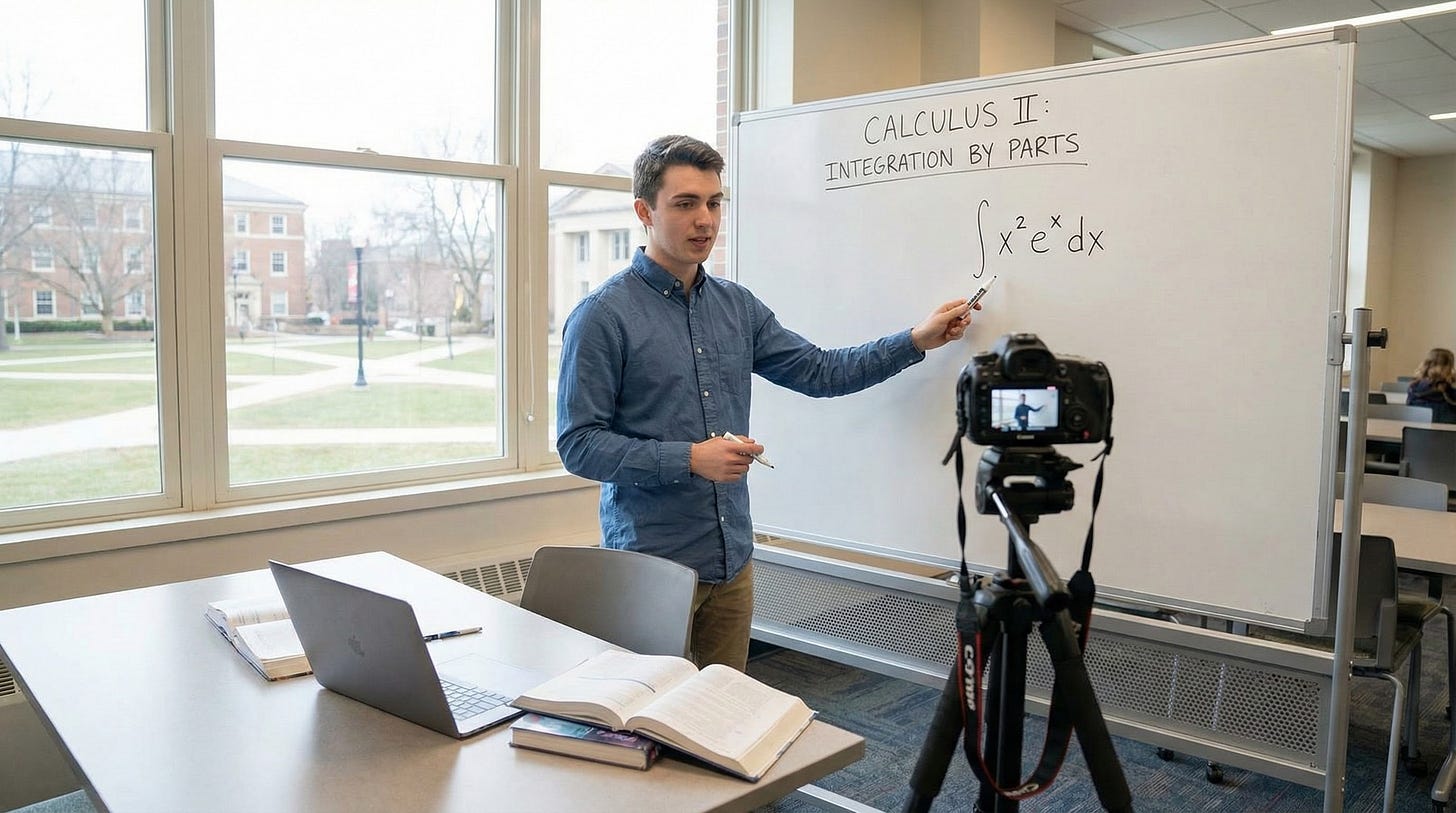

The educational vlog—the video log—offers a practical alternative. Students record themselves thinking aloud, explaining concepts, demonstrating processes, or reflecting on learning experiences. Unlike text, video preserves the embodied reality of thinking: the visible struggle to articulate complex ideas in a physical presence that anchors assessment in a particular person and moment.

In Part 1 of this series, I examined the design critique as a comprehensive model for AI-resistant assessment. But many of my readers asked: How do we implement this at scale? The design critique requires synchronous interaction, which becomes logistically impossible beyond certain enrollment numbers. The vlog is one potential answer. It preserves many of the critique’s strengths while distributing the work across asynchronous platforms and peer review structures, making it workable for instructors managing classes of 50, 100, or more students. Maybe even more importantly, it is one of the few AI-resistant methods that can be implemented in an online learning environment.

From Constructivism to the Multimodal Turn: A Brief History

The educational vlog did not emerge as a reactionary measure against generative AI. Its pedagogical foundations stretch back decades, rooted in constructivist learning theory and the multimodal literacies movement. Understanding this lineage is essential for recognizing that vlogs are not simply “essays on camera” but represent a fundamentally different approach to demonstrating successful learning.

Constructivism, drawing from the work of Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky, posits that knowledge is not transmitted passively but constructed actively by the learner through experience, reflection, and social interaction. When a student creates a vlog, they engage in what researchers call “learning by design.” They must organize information, select visual aids, sequence ideas for clarity, and articulate concepts in their own voice. This process demands synthesis and evaluation, which correspond to the upper tiers of Bloom’s Taxonomy. The student is not recalling facts but building a representation of their understanding.

The second lineage comes from the New London Group’s work on multiliteracies in the 1990s. This framework questioned education’s traditional focus on text over other communication methods. Multimodality theory argues that meaning is communicated through multiple modes: linguistic, visual, audio, gestural, and spatial. Traditional academic assessment relied almost exclusively on the linguistic mode, ignoring the other channels through which humans naturally communicate and think.

The educational vlog integrates these modes. It combines the gestural (body language, facial expression), audio (tone, pitch, hesitation, prosody), and spatial (physical context, environment, props) with the linguistic mode. This multimodal density allows for a more holistic evaluation of student learning. More importantly, it requires students to “transduce” knowledge—to move it from one mode (reading a textbook, attending a lecture) to another (speaking, demonstrating, showing). This transduction process is cognitively demanding and requires deeper mastery than simple intra-modal transfer, such as text to text.

By the early 2010s, platforms like YouTube had normalized video as a dominant form of communication for younger generations. Educational institutions began experimenting with vlogs for language learning, where they helped students develop oral fluency and confidence. But the application remained narrow until the pandemic forced a massive, involuntary experiment in video-mediated learning. Instructors discovered that video assessment, when designed properly, offered something text could not: proof of human authorship through embodied presence.

Why Vlogs Resist Artificial Intelligence

The resilience of vlogs relies on three specific factors: embodied cognition, multimodal complexity, and the friction barrier of video fabrication.

Current generative AI excels at producing linguistic artifacts: text that follows grammatical conventions, exhibits appropriate tone, and deploys domain-specific terminology. But AI systems are “ears-off” and “eyes-off” in a fundamental sense. They process data tokens, not sensory experiences. An AI can simulate a description of physical experience, but it cannot have the experience itself. A student vlog captures the “messy” reality of physical presence: nervousness, excitement, hesitation, the struggle to articulate complex thoughts, the search for the right word, and the embodied gestures that accompany explanation. These are all authentic markers of human learning.

The multimodal nature of video creates what researchers call “semiotic complexity.” When a student speaks, their message is conveyed not just through words but through dozens of non-verbal channels simultaneously. Their eye gaze patterns reveal cognitive processing—looking away to access long-term memory, scanning notes, or maintaining artificial steadiness. Their vocal prosody, including the rhythm, pitch, and pacing of speech, differs markedly between authentic spontaneous synthesis and the performance of reading someone else’s words. And their facial expressions and hand gestures either align naturally with their verbal content or exhibit the slight temporal mismatch characteristic of performed speech.

While deepfake technology advances, the effort required to generate a convincing academic-quality deepfake video of a specific student delivering a complex, personalized analysis remains orders of magnitude higher than generating a text essay. This creates a friction barrier that discourages academic dishonesty. More importantly, the assignment itself can be designed to exploit AI’s current limitations. Requiring students to interact with their immediate physical environment, such as pointing to specific features in their neighborhood, demonstrating a physical process with their hands visible, or responding to very recent events, grounds the assessment in a reality that AI cannot currently fabricate.

The Taxonomy of Educational Vlogs

Educational vlogs serve distinct pedagogical functions depending on their structure and timing. Understanding these variations allows you to select the approach that best aligns with your learning objectives.

The Reflective Log documents the learning journey over time. Common in practicum-based courses like nursing, teaching, or social work, these videos require students to record regular entries reflecting on their experiences bridging theory and practice. A nursing student might record a weekly reflection on clinical rounds, analyzing how theoretical knowledge about patient communication manifested in actual bedside encounters. The assessment focuses on metacognitive awareness, such as the student’s ability to recognize their own learning processes, identify moments of confusion or insight, and connect abstract principles to concrete situations. These logs are inherently difficult to fake with AI because they require specific, personalized experiences unfolding over weeks or months.

The Explainer Video leverages what’s known as the Feynman Technique: if you cannot explain something simply, you do not understand it deeply. Students must teach a course concept to a lay audience, translating academic language into accessible terms without sacrificing accuracy. This format exposes the “illusion of competence” that plagues passive learning. A student might understand a concept well enough to recognize it on a multiple-choice exam but struggle to explain it coherently without jargon. The act of teaching forces reorganization of knowledge into a communicable structure. The best explainer videos show not just content knowledge but pedagogical awareness. They anticipate audience confusion, provide relevant analogies, and build understanding incrementally.

The Process Documentary makes visible the thinking behind problem-solving. Students film themselves working through a mathematical proof, debugging code, conducting an experiment, or creating a physical object while narrating their decision-making process in real time. This format assesses procedural knowledge and strategic thinking rather than just final answers. When a student explains, “I’m choosing this approach because...” or “I got stuck here, so I’m trying...” they reveal their cognitive strategies. These moments of uncertainty and course-correction are precisely what AI-generated solutions obscure. A student can submit a flawless lab report generated by AI, but filming themselves actually conducting the experiment and explaining their observations as they occur provides irrefutable evidence of authorship and engagement.

The Reaction or Critique Video requires an immediate, unscripted response to readings, lectures, or current events. Students might record themselves reading an article for the first time, pausing to comment on surprising claims, questionable evidence, or connections to other course material. These videos prioritize spontaneous critical thought over polished regurgitation. The assessment values the quality of questioning and the ability to engage critically with new information, not the production of a final, refined argument. This format is particularly effective for detecting AI use because authentic reactions include false starts and moments of visible thinking that scripted responses cannot convincingly simulate.

Integrating Vlogs into Your Syllabus

The successful deployment of video assessment requires careful scaffolding. Students need time to develop both technical competence and comfort with the medium. Throwing students into high-stakes video assessment without preparation creates anxiety and often produces poor results that reflect technical struggles rather than learning deficits.

I recommend a three-phase approach that builds confidence incrementally. During the first three weeks of the semester, assign a low-stakes introduction video. The prompt is deliberately simple: “Introduce yourself and show us your workspace or study companion.” This is graded pass/fail on completion only, with no evaluation of content. The goal is purely logistical. It focuses on troubleshooting technical issues with lighting, audio, and uploading while reducing camera anxiety. This initial assignment establishes that video is a normal, recurring expectation in the course rather than a high-stakes novelty.

The middle phase, from week four through eight, introduces formative assessment through what I call “the one-minute paper.” Students record a 60-second video each week summarizing a key concept or articulating their “muddy point”—something they found confusing or difficult. These videos receive peer feedback only, with no formal grading beyond participation credit. This builds the habit of regular video creation while providing multiple low-pressure opportunities to practice synthesis and brevity. Students learn to articulate complex ideas concisely, a skill that proves valuable in later assignments.

The summative phase occurs in the final weeks of the semester with a capstone vlog or video essay that synthesizes course material. This assignment is longer (5-7 minutes), more complex, and formally graded using a comprehensive rubric. Because students have already completed multiple video assignments, the medium itself no longer poses a significant challenge. They can focus cognitive resources on content rather than wrestling with technical logistics. To verify authorship and process, instructors can require students to submit notes or drafts alongside the final video.

For large-enrollment courses, timing and distribution are critical. If you have 150 students submitting 5-minute videos, that represents over 12 hours of viewing time, which is clearly unsustainable for a single instructor. This is where strategic design becomes essential. First, not all videos require full viewing. For formative assessments, spot-checking 30-second segments suffices to verify participation and general competency. Learning management systems and platforms like YouTube allow playback at 1.5x or 2x speed without pitch distortion, effectively halving review time. Second, and most importantly, peer review distributes the evaluation load across the entire cohort, a topic I’ll address in more detail in the implementation toolkit.

The assessment criteria should explicitly prioritize content over production quality. A balanced rubric might allocate 40% to content accuracy (proper use of terminology, factual correctness, depth of understanding), 30% to critical synthesis (ability to connect ideas, apply concepts to new contexts, demonstrate metacognitive awareness), 20% to communication clarity (logical organization, effective verbal delivery), and only 10% to basic technical audibility—a pass/fail threshold ensuring the video can be heard and seen. This weighting signals clearly that ideas matter more than cinematic polish, reducing anxiety and focusing effort on learning objectives.

Conducting Vlog Assessments Successfully

The execution of video assessment requires attending to both pedagogical and logistical considerations. The choice of platform, the structure of prompts, and the feedback mechanisms all influence outcomes.

Platform selection matters more than many instructors initially realize. The technology should be invisible, allowing students to focus on content rather than wrestling with software. VoiceThread works well for narrated presentations where students comment on uploaded slides or images. For institutions already using Canvas or Blackboard, the native video submission tools offer the simplest option, though they often lack sophisticated peer review features. Whatever you use, make sure it complies with your institution’s policies.

The assignment itself is your primary defense against AI fabrication. Generic prompts inviting recall of information invite generic, AI-generated responses. Effective video prompts require three elements: contextualization, personalization, and process revelation.

Contextualization grounds the assignment in the student’s immediate environment. Rather than “explain erosion,” the prompt reads: “Find an example of erosion or weathering in your local neighborhood. Film it, and explain the geological forces at play using terminology from Chapter 4. Point to specific evidence visible in your video.” This forces interaction with the physical world that is AI-proof.

Personalization requires students to engage with their own learning experience rather than presenting sanitized analyses. Instead of “discuss the themes in the novel,” try: “Which specific concept in this module was hardest for you to grasp? Why was it difficult? How did your understanding change after the second reading or discussion?” AI can simulate reflection, but it lacks the specificity of genuine struggle and the particular details of individual learning trajectories.

Process revelation focuses assessment on thinking rather than conclusions. For problem-solving disciplines, require students to record themselves working through the solution in real time: “Record yourself solving this problem on paper. Talk through why you chose this formula and what you’re thinking at each step. If you get stuck, explain your confusion.” The moments of uncertainty and the corrections—these are the markers of authentic engagement.

Integration of current events exploits AI’s knowledge cutoff and tendency toward generic responses. “Analyze yesterday’s speech using the rhetorical framework from class. Quote specific lines and explain their rhetorical impact.” The 24-48 hour window makes it difficult to find or generate generic analyses, and the requirement to quote specific language grounds the assessment in careful attention to primary sources.

Feedback on video can and should use video as well. Paradoxically, giving verbal feedback is often faster than typing marginal comments. Instructors can speak at roughly 150 words per minute, far exceeding typing speed. A one-minute audio comment conveys more nuance, tone, and detail than five minutes of written feedback. More importantly, audio feedback builds what researchers call “instructor presence.” Students feel more connected to the instructor when they hear their voice, which improves motivation and persistence. Most learning management systems now include built-in audio/video recording for feedback, streamlining the process

Limitations, Pitfalls, and Honest Challenges

Video assessment is not a catch-all solution. It introduces distinct challenges that require acknowledgment and mitigation strategies. We must name these explicitly rather than presenting video as a minimal-friction solution.

First, the scalability challenge remains real despite peer review mechanisms. Even with distributed grading, video assessment requires more instructor time than machine-gradable formats. The initial setup demands significant front-loaded effort. For instructors already overwhelmed with grading obligations, this additional burden can feel prohibitive. The mitigation is to start small: replace one written assignment with video in a single course, refine the process, then expand. Attempting to convert an entire curriculum to video assessment simultaneously invites burnout and poor implementation.

Second, equity issues pervade video assessment if not addressed proactively. Unlike the design critique, where equity concerns focus on verbal confidence and familiarity with academic discourse, video assessment introduces “videoclassism”—the fear students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds may feel regarding the judgment of their visible living environments.

Not all students have access to private spaces for recording. Some possess only low-quality cameras on older devices, making technically adequate videos difficult to produce. The assessment risks measuring access to resources rather than learning. This can be addressed through a “menu of options”: students can submit audio-only recordings, use virtual backgrounds, film objects or screens rather than their faces, or request accommodations for recording in campus spaces. And the rubric must explicitly de-prioritize production quality, focusing overwhelmingly on content and synthesis.

Third, camera anxiety is pervasive and genuine. Many students experience significant distress at the prospect of being watched and evaluated on video. This anxiety is not mere nervousness but can trigger physiological stress responses that interfere with cognitive performance. Students with body dysmorphia, social anxiety, or gender dysphoria may find mandatory face-to-camera requirements particularly harmful. For neurodivergent students, maintaining neurotypical eye contact or body language can cause masking fatigue. The solution is flexibility without compromising learning objectives. Avatar-based software, puppet alternatives, or screen-focused demonstrations preserve the assessment’s core purpose, such as demonstrating authentic synthesis and process, while accommodating diverse needs. And it is critical to remove ableist standards from rubrics that require “appropriate” eye contact or stillness.

Fourth, the “reading a script” problem requires vigilance. Students can generate AI scripts and read them on camera, technically fulfilling the assignment while circumventing its purpose. Detection requires attention to forensic cues that distinguish scripted from spontaneous speech. Cognitive load theory provides useful markers: authentic spontaneous speech is characterized by natural disfluencies—”ums,” “ahs,” false starts, and pauses for thought. These mark cognitive effort as the brain retrieves and synthesizes information in real time. In contrast, reading a script often produces “super-fluency”—a steady, rhythmic cadence lacking natural pauses. Students reading AI-generated scripts also frequently use complex sentence structures rare in natural oral communication: “Therefore, it can be concluded that...” or “Furthermore, the dichotomy presented...”

Authentic student speech tends toward simpler, more clausal constructions using “and then” and “so” rather than elaborate subordination. Eye gaze patterns provide additional evidence: looking away to access long-term memory differs from the horizontal scanning that indicates reading. For high-stakes assessments, consider a hybrid approach: all students submit videos, but the instructor flags suspicious submissions exhibiting perfect script reading or content-ability mismatches. Only flagged students (typically a small percentage) are called for brief synchronous defenses where they must discuss their video extemporaneously. The possibility of this verification step acts as a powerful deterrent.

Fifth, technical failures happen. Videos don’t upload, files corrupt, and platforms malfunction. You need explicit policies for these situations before they occur. Allow 48 hours past the deadline for technical issues with required documentation (screenshots of error messages), and maintain a backup submission method, such as allowing students to email large files directly or use file-sharing services if the platform fails. Building in this flexibility prevents penalizing students for problems beyond their control while discouraging false claims of technical difficulties.

Finally, the shift to video represents a fundamental change in classroom culture that requires buy-in from students. Some will resist, viewing it as unnecessary or intrusive. This resistance often stems from a lack of clarity about purpose. Explicit discussion of why video assessment serves learning objectives—not just authentication—helps build acceptance. Demonstrating that you watch and engage with their videos rather than treating them as mere submission artifacts further establishes that the format matters pedagogically, not just administratively.

Your Vlog Implementation Toolkit

What follows is a practical framework for implementing video logs in your course. Treat this as an adaptable structure rather than a rigid prescription.

Step 1: Define Learning Objectives and Select Video Type

Begin by clarifying what you want students to demonstrate. If the goal is a metacognitive awareness of learning processes, reflective logs make sense. If you’re assessing understanding of complex concepts, explainer videos work better. For procedural knowledge, process documentaries provide the clearest evidence. Match the video format to your actual learning objectives rather than selecting video for its own sake. Map your major assignments to specific video types, considering how each assignment builds toward course-level competencies.

Step 2: Infrastructure and Onboarding

Select a platform based on your institution’s existing technology ecosystem and the video type you’ve chosen. Test the platform yourself: record, upload, and review a sample video to identify potential student pain points. Create a brief tutorial video or written guide showing students exactly how to record and submit. Include screenshots or screencasts demonstrating each step. Identify campus resources for students lacking adequate technology (library recording booths, equipment checkout) and communicate these resources in your syllabus and first-day materials.

Once the semester begins, explain why you’re using video assessment. Frame it pedagogically: video allows you to assess thinking processes, not just final answers; it develops professional communication skills; and it provides evidence of authentic engagement. Show examples of effective student videos from previous semesters (with permission). In week two, assign the introductory video graded pass/fail on completion. Require only that students introduce themselves and show something in their physical space. This serves both as a technical check and as an anxiety reducer. Provide feedback on technical quality only: “Great—I can see and hear you clearly” or “Your audio is too quiet; try recording closer to your microphone.” This establishes norms without content pressure.

Step 3: Design Authenticity-Resistant Prompts

Design assignments that exploit AI’s current limitations. Require physical interaction with the environment, personalized reflection on specific learning experiences, real-time problem-solving with visible thinking, or response to very recent events. Include requirements that ground the video in the student’s actual context: “Show us your setup,” “Point to specific evidence,” “Explain what you’re doing as you do it.” Require submission of supporting materials, such as notes, outlines, or drafts, that allow you to trace the development of ideas and verify that the student engaged in the process, not just the product.

Step 4: The Process-First Rubric

Develop a rubric that makes your values explicit. Weight content and synthesis far more heavily than technical production. A recommended distribution: Content Accuracy (40%), Critical Synthesis and Application (30%), Communication Clarity (20%), Technical Audibility (10%). Define each criterion clearly with examples of what strong, adequate, and weak performance looks like. For “Communication Clarity,” specify that you’re evaluating logical organization and effective verbal delivery, not production values like lighting or editing. Share this rubric when you announce the assignment and reference it explicitly when providing feedback.

Step 5: The Feedback Loop

For low- and medium-stakes assignments, use peer review to distribute the evaluation load. Before peer review begins, conduct a norming session: have all students grade the same sample video using the rubric, then discuss why scores differed and calibrate expectations. Each student reviews three peers anonymously. The final grade is calculated as a weighted average of peer scores, with algorithmic checks to exclude outliers (for example, scores more than two standard deviations from the mean). Students also complete self-assessments using the same rubric, which research shows enhances metacognitive awareness. You become a moderator, grading only videos where peer scores show high variance or where students flag concerns.

Respond to video with video or audio feedback when possible. Record brief (1-2 minute) responses addressing what the student did well, one specific area for improvement, and a question that pushes their thinking further. This verbal feedback conveys more nuance and builds instructor presence more effectively than text comments. For peer-reviewed assignments, synthesize the peer feedback and add your own observations. If providing written feedback, make it substantive and personalized. Reference specific moments in their video, quote phrases they used, and acknowledge their particular examples or applications. Deliver all feedback within one week of submission to maintain momentum and relevance.

Step 6: Progressive Complexity

Design your video assignments to increase in complexity and stakes as the semester progresses. Early assignments should be brief, focused, and low-stakes. Middle assignments can be longer and require more synthesis but remain formative in nature. The final assignment should be comprehensive, synthesizing course material and demonstrating mastery. This progression allows students to develop competence with the medium while gradually raising expectations. By the final assignment, the technology itself should fade into the background, allowing students to focus entirely on demonstrating their learning.

Why the Effort Matters

The shift to video assessment represents more than a defensive measure against AI fabrication. It embodies a necessary pedagogical reorientation toward process, presence, and authentic demonstration of learning. For decades, we relied on text-based artifacts as proxies for thinking, and that reliance worked reasonably well when producing such artifacts required genuine engagement with ideas. That era has ended. We now face a choice: escalate surveillance and detection methods in an adversarial arms race with technology, or fundamentally rethink what we assess and how we assess it.

Video logs offer a path forward that is both pragmatic and pedagogically sound. They require human presence and embodied performance that current AI cannot convincingly reproduce. They develop communication skills that prove increasingly valuable in professional contexts. And they make the thinking processes visible that text-based assessment often obscures. Most importantly, when designed with peer review structures and clear rubrics, they scale to larger enrollments without becoming administratively overwhelming.

The challenges are also real. Video assessment demands more from instructors and students than machine-gradable formats. It requires confronting equity issues around technology access and camera anxiety. It necessitates cultural shifts in how we conceive of academic work and what counts as legitimate evidence of learning. But these challenges are not reasons to avoid video assessment; they are opportunities to design better, more inclusive, and more meaningful evaluation practices. The alternative—clinging to text-based artifacts that no longer reliably show learning—serves neither students nor the integrity of our disciplines.

In an age when AI can produce text that mimics understanding, video logs return us to something fundamental: the recognition that learning is a human activity, inseparable from embodied experience, physical presence, and the messy reality of thinking-in-progress. This is not a retreat from technology but a strategic deployment of it. It uses video not to replace human interaction but to capture and amplify the distinctively human dimensions of learning that remain, for now, beyond algorithmic replication.

The images in this article were generated with Nano Banana Pro.

P.S. I believe transparency builds the trust that AI detection systems fail to enforce. That’s why I’ve published an ethics and AI disclosure statement, which outlines how I integrate AI tools into my intellectual work.