The Evolution of Educational Values

A Personal Perspective on AI and Writing

Recently, I’ve observed an increasing number of educators sharing their thoughts on SubStack about integrating AI into teaching creative writing. A common thread emerges: the concern that AI technologies might undermine traditional educational values and skills. This anxiety reflects a broader discussion about the changing nature of education and the role of human creativity in an increasingly digital world.

Matthew Kirschenbaum’s concept of the “Textpocalypse,” introduced in an article in The Atlantic, captures these concerns effectively. He describes an impending “tsunami of text and content” generated by AI systems, raising valid questions about the future value of human-authored writing and the increasingly complex relationship between human and machine-generated content.

I deeply empathize with educators who have dedicated their careers to fostering human authorship and creative writing and now fear the loss of many of these values. However, drawing from my personal experience with radical technological change, I’d like to offer a different, and potentially controversial, perspective on this issue.

What if our current valuation of human-authored writing merely represents a transient phase in our intellectual evolution?

The skills and values we consider essential in education have never remained static. Many capabilities once deemed crucial decades ago now hold little practical relevance. This pattern of change suggests that our present educational priorities even within the context of something as fundamental as creative writing may not maintain their significance indefinitely.

A Personal Journey Through Educational Change

My career path illustrates how dramatically educational values can shift over time. I began in a field that's barely recognizable today, as technological advances have fundamentally transformed the skills I acquired during my graduate studies and early academic work.

In the mid to late 1980s, I studied at the Vienna University of Technology, specializing in the pedagogy of “Descriptive Geometry” - a discipline with a rich tradition also known as the “Vienna School of Geometry.” Our role was to teach engineering and architecture students the precise art of hand-drawn technical drawings.

It is important to point out that the curriculum demanded extraordinary precision and patience. For example, engineering students learned to determine the exact radius of curvature in cylindrical intersections using only ruler and compass. And architecture students mastered every aspect of three-point perspective techniques for accurate architectural renderings of complex curved surfaces.

This was a time-consuming craft. A single drawing might require days of careful and laborious work, culminating in a final ink rendering where a single mistake could cause starting over completely. Unfortunately, I no longer have any of my own drawings. The University archive kept the better ones, and I lost the ones I had during a move long ago.

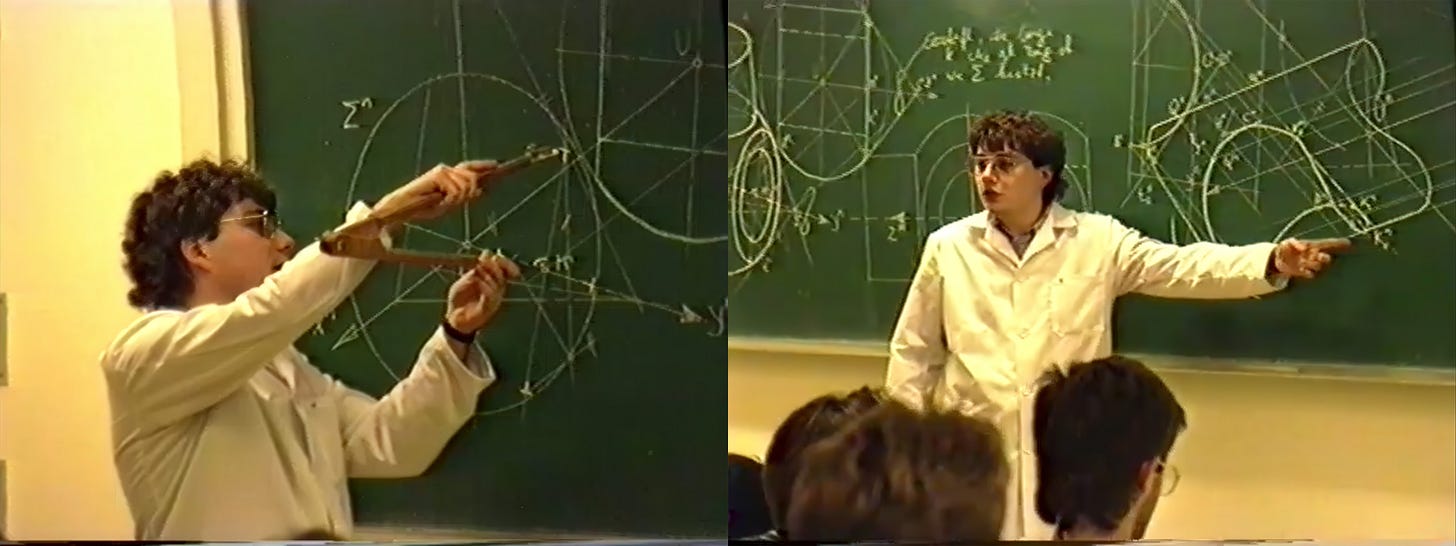

What I do have, however, is a video recording of one lecture I gave as a student in 1989. You can see some screenshots included here. And if you don’t mind the inferior quality recording and German language, you can watch my full lecture on YouTube, where I published it as an unlisted video.

I also still have the compass I used in this video; you can see it in this post’s cover image. The compass was custom made by a local carpenter so that it would provide the required accuracy on the blackboard. And in case you are wondering, we wore lab coats during our lectures. This wasn’t for show - we used colored chalk on the blackboard, and these stains were impossible to remove from street clothes. The lab coats were essential for protecting our clothing.

The Parallel with Today’s AI Transition

As computer-aided design (CAD) systems became more accessible in the mid-1980s, our initial response mirrored current reactions to AI in writing. We argued that hand-drawing skills were fundamental to developing critical evaluation abilities in engineers. We believed architects couldn’t truly understand spatial relationships without manual drawing experience. These arguments sound strikingly similar to current debates about AI and writing.

However, technological progress gradually and relentlessly challenged these assumptions. Our department eventually merged with mathematics, and our courses were significantly reduced in scope. I adapted to these changes, moving on to new challenges that bore little resemblance to my original training.

Today, courses about descriptive geometry remain in the curriculum in many universities, but they are now specialized components of engineering and architectural education, not fundamental ones. And I sometimes wonder if these courses focus more on preserving cultural heritage than on teaching practical skills.

Lessons for the Present

Nevertheless, the quality of engineering and architectural work hasn't diminished with the transition to CAD systems. Instead, these tools have enabled new possibilities while maintaining professional standards. And our educational values have evolved alongside these technological changes.

Engineers can now model complex mechanical systems with unprecedented precision, testing multiple iterations before production. Architects design buildings that would have been nearly impossible to conceptualize with traditional drawing methods. The tools have changed, but the fundamental understanding of spatial relationships and engineering principles remains crucial - it’s just expressed through different means.

I believe this history can offer a valuable perspective on current debates about AI and writing. Just as the importance of hand-drawn technical drawings proved less critical than we imagined, perhaps we should examine our assumptions about the absolute necessity of traditional human authorship in writing.

The evolution of educational values isn’t about loss, but transformation. While certain traditional skills may become less central, new capabilities and forms of creativity emerge. The key lies in maintaining an open mind while ensuring we prepare students for the future they’ll actually encounter, not the past we’re familiar with.

This perspective doesn’t aim to dismiss current concerns about AI in education, but to suggest that a broader historical lens could benefit our view of these changes. Perhaps the question isn’t whether AI will devalue human writing, but how it might transform our understanding of authorship and creativity in ways we haven’t yet imagined.